Volume 3, Issue 2 (2023) Fall 2023

“Education is freedom.” -Freire.

In 1994 Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act which amended the Higher Education Act of 1965. In doing so, all incarcerated people were banned from receiving Pell grants or financial aid for higher education. Four years later Congress extended the ban to any student with a state or federal drug conviction. Even though less than 1% of federal education funding went to incarcerated students, the “tough on crime” mantra of the day led to the elimination of most prison education programs originally developed in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 2015 a pilot program allowing Pell grants for incarcerated students began at a select group of facilities and institutions. When the FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) Simplification Act was passed in 2020, the success of the pilot programs gave way to Congress reauthorizing access to Pell grants to students incarcerated in federal or state penal institutions and students who are subject to involuntary commitments. As of July 2023, all provisions of the Act relating to incarcerated students are active, meaning that for the first time in almost 30 years, individuals enrolled in approved prison education programs (PEPs) are eligible for federal student aid. Provisions of the FAFSA Simplification Act also changed the definition of prison education program and now requires approval, oversight, and various other procedures.

Under the FAFSA Simplification Act all PEPs must be accredited and offer the same quality of education in prison as they do outside of prison. So, readers, why am I giving you this information? As this is my inaugural issue as Editor-in-Chief, I would like to not only share this critical development but also leave you with a call to action. As a criminologist, I’ve spent the better part of the last 15 years working with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. In the incarceration capital of the world, I have witnessed the potential lost to incarceration and it’s collateral consequences. Yet, one thing we have known for decades is that education not only reduces recidivism in the individual learner, it increases public safety, and impacts families for generations¹. It can transform the lives of over 5 million children with incarcerated parents, while strengthening the communities in which they live. Data also shows that for every dollar spent on education while individuals are incarcerated, taxpayers ultimately save five dollars in the future. Furthermore, current estimates indicate lifting the financial aid ban will allow almost 800,000 incarcerated individuals access to PEPs, amounting to a less than 1% increase in the programs budget. As more schools open their classrooms to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated students, we must, not only, create a welcoming learning environment, but also encourage and support undergraduate research and scholarly creative endeavors. Historically, few educational programs or PEPs have offered courses or programs that allow incarcerated students to conduct undergraduate research. Often students have limited access to technology and research materials, with the Vera Institute reporting less than 20% of PEP students having access to academic research material.¹ Engaging in scientific inquiry, evaluating sources, and critical thinking are all fundamental to undergraduate education. It is crucial that colleges developing PEPs, not only provide quality academics, but also include intellectual inquiry through undergraduate research with access to meaningful resources.

When given the opportunity, these students will thrive. I’ve seen the hunger for knowledge and transformative power of education. Therefore, my call to you, readers, is to do what we do best, teach, research, and serve all individuals who seek to learn. As U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona stated, education creates “meaningful opportunities for redemption and rehabilitation that improve lives, strengthen communities, and reflect America’s ideal as a nation of second chances and limitless possibilities.”²

Alesa Liles, Ph.D., MSW

Editor-in-Chief

¹ https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/second-chance-pell-five-years-of-expanding-access-to-education-in-prison-2016-2021.pdf

² https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-launch-application-process-expand-federal-pell-grant-access-individuals-who-are-confined-or-incarcerated

Front Matter

Alesa Liles

Research Outreach Interdisciplinary Activity to classify olive oil blends integrating multicolor imaging, image processing, and machine learning

Allan Abraham and Kameshwaran Balachandran

Measuring the Relationship between the Big Five Personality Traits and Time Spent on Social Media

Jenna Kaitlyn Cordaro

Contending with COVID: Examining Levels of Anxiety Among College-Aged Adults in the Wake of the Pandemic

Madison C. Harris

Back Matter

Alesa Liles

Editor-in-Chief

Alesa Liles, Georgia College & State University

Managing Editor

Kelly P. Massey, Georgia College & State University

Associate Editor

Doreen Sams, Georgia College & State University

Editorial Board

- Amy Buddie

- Kennesaw State University

- Jordan Cofer

- Georgia College & State University

- Ashley Hagler

- Gaston College

- Kasey Karen

- Georgia College & State University

- Jill Kinzie

- Indiana University

- Huda Makhluf

- Precision Institute National University

- Marisa Moazen

- University of Tennessee-Knoxville

- Niharika Nath

- New York Institute of Technology

- Jeanetta Sims

- University of Central Oklahoma

- Kate Theobald

- University of West Georgia

- Charles Watson

- Association of American Colleges & Universities

Acknowledgements

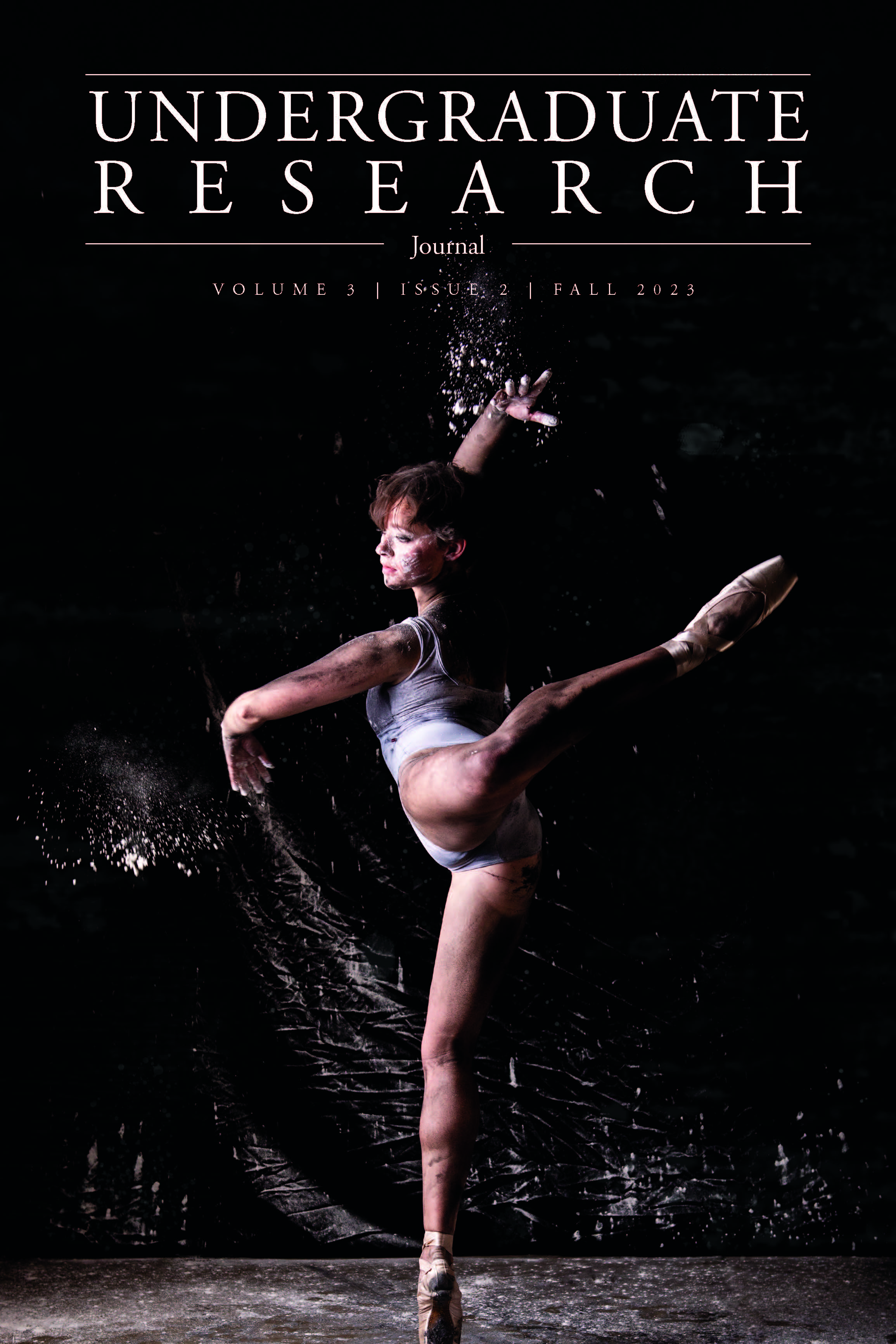

Cover Art

Juliana Pinson, Middle Tennessee State UniversityValkyrie Rose, Middle Tennessee State University

Ashes to Ashes

Back Cover Art

M. Suits,Hope